Talking About Personal Responsibility

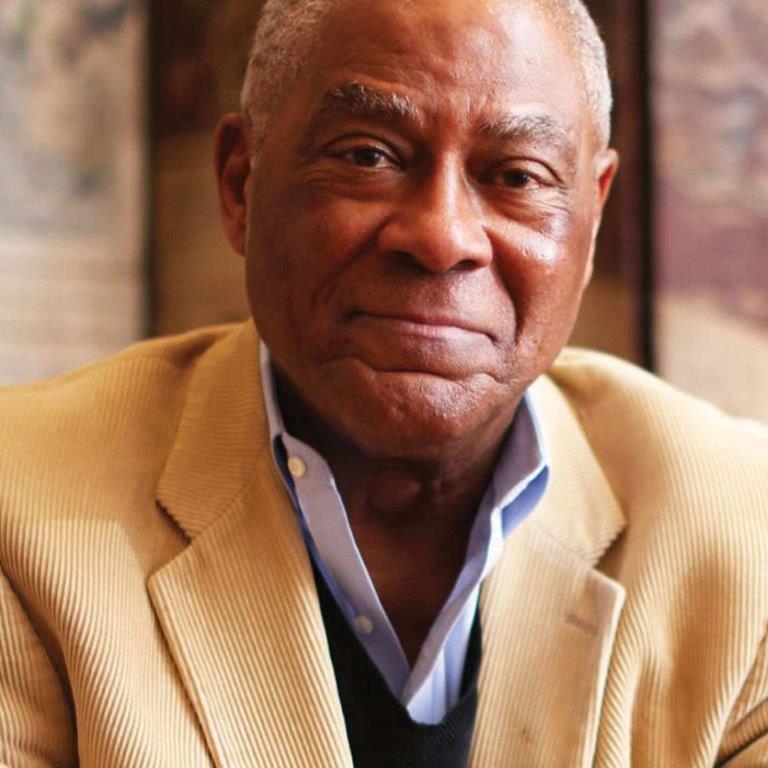

- Thomas Jones

- Oct 20, 2021

- 5 min read

On September 30, 2021 The New York Times published a book review by Matthew Desmond titled "Dasani Showed Us What It's Like to Grow Up Homeless. She's Still Struggling", which discusses the book "Invisible Child: Poverty, Survival and Hope in an American City" written by New York Times reporter Andrea Elliott. A brief synopsis follows.

"Best we can tell, there are 1.38 million homeless school children in the United States. About one in 12 live in New York City. Several years ago, readers of this paper got to meet one, an 11-year-old Black girl with an unforgettable name: Dasani. For five straight days in December 2013, the front page of The New York Times focused on a child who lived in the Auburn Family Residence, a homeless shelter in Brooklyn...Dasani's charm contrasted brutally with her degrading and dangerous surroundings. Her family -- [mother] Chanel and her husband Supreme, along with their eight children -- lived in a single room at Auburn...The story was an indictment of the city's shelter system and of the Bloomberg administration, on whose watch the number of homeless families had increased by 80 percent. It was the kind of story you couldn't shake. That winter, everyone was talking about Dasani...Her schoolmates crowned her 'homeless kid of the year'. The Times forwarded an outpouring of donations to the Legal Aid Society, which created a trust for the children, a decision that irked Chanel, who was barred from accessing the funds...So what happened to Dasani? Elliott picks up the story in "Invisible Child"...Elliott spent eight years working on the book, following Dasani and her family everywhere: at shelters, schools, courts, welfare offices, therapy sessions, parties.. 'Whatever power came from being in The Times', Elliott writes, 'was no match for the power of poverty in Dasani's life'...Chanel had been desperately poor for most of her life, as had her mother, who for years smoked crack cocaine. Chanel herself became hooked on opiates after a doctor prescribed OxyContin...Supreme soon began swallowing the numbing pills too. Heroin had been his parents' drug of choice. Throughout the book, Chanel and Supreme battle addiction and submit to joblessness, yet they refuse to visit soup kitchens or apply for disability benefits, for which they and at least two of their children would likely have qualified...The family is a picture of chaos and love. When Chanel secures a housing voucher that subsidizes rent, the family moves into a Staten Island apartment with multiple bedrooms. But at night, the children drag their mattresses into the living room and sleep as they did at the shelter: as one intertwined heap...Elliott registers echoes across generations, the phrase "the same" serving as the book's steady cadence. When Chanel and Supreme sign in for a meeting with child protective services, it happens in the same office where Supreme was processed as a boy. When Dasani's stepbrother is arrested for assaulting a middle-aged woman, he's booked at the same police precinct Supreme once was. Chanel is reminded of the weary, looping rhythms of poverty every time she steps into a homeless intake and sees a familiar face. 'It's a cycle,' she tells Dasani. 'It already happened. It's just coming back around'. But will it come back around for Dasani? Her best shot to break the cycle arrives when she is admitted to the Milton Hershey School, a Pennsylvania boarding school for low income children founded by the chocolate magnate. Drawing from its large trust, Hershey invests nearly $85,000 a year in each of its students, providing them with housing, medical and dental care, clothing and food, and a large support staff. At Hershey, Dasani lives in a large home with a dozen other girls and two boys, as well as two house parents, who reassure their charges that they no longer need to guard their food at dinnertime. As Dasani begins to thrive at Hershey, her family back in New York begins to unravel...Her 7-year-old brother runs away...Child protective services bars Chanel from the family home, mainly on account of suspected drug use...Supreme...is arrested. Social workers send the children to three different foster homes. Dasani blames herself. She lashes out, bloodying a girl's nose and risking expulsion...Elliott often points to the role of a dysfunctional welfare state...The past, too, haunts the present. Dasani's great-grandfather earned three Bronze Service Stars as an auto mechanic in World War II, but after the war ended, racism kept him from securing a union job or buying a home. The federal government effectively nullified his veteran's mortgage by redlining his neighborhood. "The exclusion of African Americans from real estate," Elliott writes, "laid the foundations of a lasting poverty that Dasani would inherit."

I listened recently to an engaging sermon by a talented young minister on the topic "Why Bad Things Happen to Good People". His biblical text was from the Book of Job wherein a virtuous and pious man is afflicted with all manner of adversity, including losing his family, his health, and his wealth. When Job challenges God to justify his suffering, God responds "Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?", but neither explains or justifies His treatment of Job. The minister concluded that God is not accountable to us, and the answer to why bad things happen to good people is part of the great "Mysterium Tremendum" -- the mystery of God -- and is not something we can change.

My point is that if we cannot prevent virtuous people from suffering extraordinary adversity, or rectify the harms they suffer, it's even less plausible to think we can intercede effectively in the sufferings of those who are irresponsible. Chanel and Supreme are drug abusers, unemployed most of the time, and have eight children they cannot take care of. Their irresponsible lifestyle is sustained by welfare and housing subsidies. To put their irresponsibility in perspective, Empire Center (a public policy think tank) reported in May 2020 that New York City public schools spend $26,588 per pupil (which is by far the highest among the 100 largest school systems in the US), which means that Chanel and Supreme's eight children cost taxpayers over $212,000 per year in public education expenditures. The recently expanded Child Tax Credit for children, payable even to the unemployed, makes Chanel and Supreme eligible for over $24,000 annually for their eight children. And if the Biden administration Build Back Better "human infrastructure" legislation is enacted, taxpayers will pay hundreds of billions more each year to support daycare, universal pre-K, free community college, and other government benefit programs. Does anyone really believe that the same government bureaucracies which run the homeless shelter system, the welfare system, and New York City public schools will run effective pre-K and universal daycare programs? Does anyone really believe increased government benefits will transform Chanel and Supreme into responsible parents?

As acknowledged by author Elliott, public expenditures so far have not achieved self-reliant and dignified lives for Chanel and Supreme, their lives just "stay the same". Elliott blames "dysfunctional welfare state and racism", which I think is nonsense. The only people I see succeed are those who take personal responsibility for their lives -- they strive to become educated, to secure employment, to live responsibly, and consciously limit family size to their capacity to be good parents. I support public assistance programs designed to help those who try responsibly to help themselves.

What do you think?

Wow. This is heartbreaking.

I think you can provide opportunity but you can't guarantee results. How do you help a family like this? Thank you for the thought provoking piece. No easy answers.