Talking About Race in America, Part 2

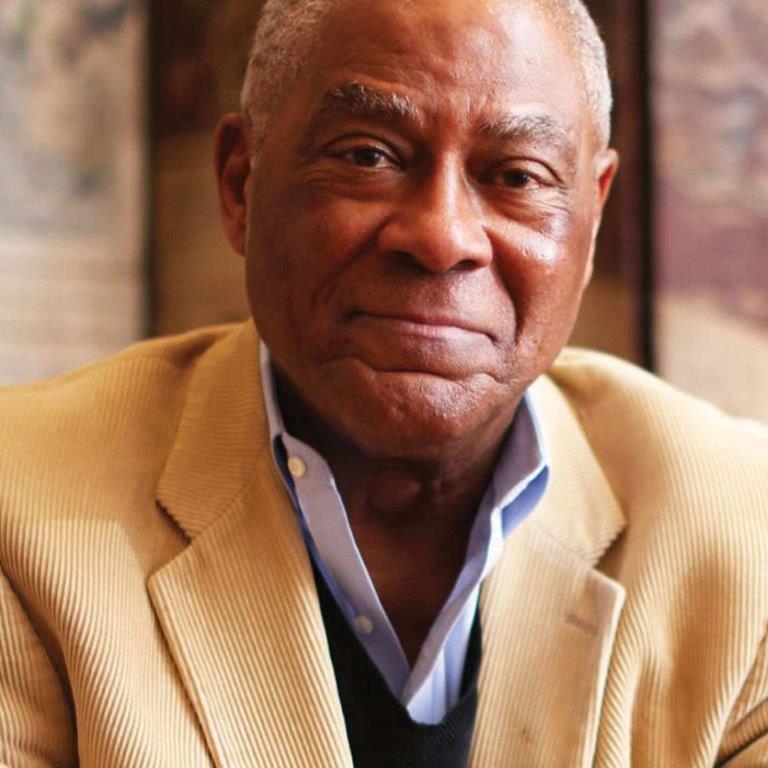

- Thomas Jones

- Jun 15, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 20, 2022

This week has seen ongoing demonstrations across the country against police brutality, creating a wave of energy for police reform legislation. Significantly, on Friday New York Governor Cuomo signed reform legislation overcoming Section 50-a which shielded police disciplinary records from public view. The new legislation opens police disciplinary records and transcripts of disciplinary hearings to public view, bans choke holds, and creates an independent public prosecutor requirement for review of all unarmed civilian deaths resulting from police actions. This is a monumental achievement, culminating a 40-year fight waged since the 1970’s.

Other significant news events this week are Nascar’s decision to ban the Confederate flag from racing events, and the actions in Richmond, Va and Lexington, Ky to remove public monuments honoring Confederate generals. The significance of these events is that it represents public demand to remove implicit symbols of white supremacy from the public domain. This is very encouraging.

My expectation is that the focus of the protests in this presidential election year will eventually turn to economic inequality, which is the fundamental underlying reason why the Covid-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected black and brown communities. Today I would like to offer a moral framework for thinking about economic fairness, and again I see a ray of sunshine for how that can be done. Let me give two examples of dividing the economic pie, and the moral choices implicit in each.

In the early 1970’s I was in the first wave of blacks entering corporate America in significant numbers. What I will call “Benevolent Capitalism” was the dominant corporate business model. Lifetime career employment was common, accompanied by generous family medical benefits, and defined benefit retirement pensions designed to replace 50-60% of preretirement income. Companies shouldered the burden of funding those defined benefit pensions, absorbing the investment risks associated with decades-long periods of pension fund accumulation and benefit payments. Most top-tier companies also invested generously in employee training and development. When Reginald Jones retired as CEO of General Electric in 1981, widely regarded as the top CEO in the country and leading one of the most highly-regarded companies, news media reports estimated his net worth at $10 million (approximately $50 million in today’s dollars). Jones was rich, but not so wealthy as to be “out of touch” with his community. One of the defining characteristics of that era was the modesty and moderation of the people at the top. People at the top did well, and a lot of people in the middle or lower tiers also did very well, in relative terms. Unfortunately, pervasive institutional racial discrimination meant that very few African Americans participated in this benevolent corporate culture in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

Then things began to change. I observed the changes occurring in tandem with the emergence of the “leveraged buy-out” (LBO) corporate raiders in the 1980’s, often funded by junk bond king Michael Milken. The excesses of this decade are perhaps best illustrated by media reports that Michael Milken’s compensation was $550 million in 1987, and the 1988 story of buyout firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts winning the $25 billion takeover of RJR Nabisco which was chronicled in the book Barbarians at the Gate. The basic modus operandi of the buyout firms was to use enormous junk bond debt to finance company acquisitions, then strip out corporate costs to increase operating cash flow for debt service and dividends. The corporate costs which were stripped were most often employee headcount, medical and pension benefits, employee compensation, employee training and development, and research & development expenditures. For the most part the LBO raiders did not create new value in the form of new products or services. Numerous mainstream corporate CEOs soon decided that they could also play the game of stripping costs, increasing cash flows, and capturing enormous compensation rewards for themselves. General Electric CEO Jack Welsh was an avid practitioner of this employee headcount reduction mentality, earning the nickname “Neutron Jack” in a twist on the US military bomb which reportedly killed people while leaving buildings and structures intact.

Fast forward thirty years and we arrive at today, and what I will call “Winner Take All Capitalism” has become the dominant corporate business model. It is not uncommon today for a Fortune 500 CEO to retire with net worth of $500 million to $1 billion or more. The number two’s in the corporate hierarchy get $250-500 million, the number threes get $125-250 million, etc. Staying with the General Electric example where CEO Reginal Jones retired in 1981 with the equivalent of $40-50 million, Fortune magazine reported that CEO Jack Welch retired in 2001 with $417 million, and CEO Jeff Immelt resigned in 2017 with $211 million after a failed tenure in which GE’s market value declined $150 billion.

Meanwhile, many workers below the top tier are getting by on modestly funded medical benefits with significant co-pays and deductibles; defined contribution retirement benefits which transfer the risks of adequate funding and investment performance to the employee; slow growth in wages; insecurity associated with outsourcing of engineering, call center, and legal research jobs to India; relocation of manufacturing jobs to Mexico, China and Southeast Asia; and insecurity associated with the growth of the “gig economy” and “independent contractor” status for workers. Should we be surprised that the news media report that opinion polls show many young people expressing doubts about our capitalist economy?

Today’s top corporate executives are usually competent stewards of the companies they inherited, but they rarely create true economic value on a scale which justifies their outsized compensation. The lion’s share of the rewards at the top are driven by stock compensation, which benefits from stock prices pushed higher by corporate cash flows diverted to dividends and stock buybacks. A defining characteristic of this Winner Take All Capitalism is that the few winners at the top are immensely better-off, and many people in the middle and lower tiers are relatively worse-off. African Americans and other people of color are underrepresented in the top of the corporate hierarchy, so communities of color are generally net losers from this Winner Take All Capitalism.

Importantly, the deleterious impact of this economic distribution also applies to middle and lower- income white Americans. It is one reason for the soaring rates of opiod and alcohol abuse and family breakdown. Think about the morality of these economic choices we are making. Is this what America should be? I urge America to return to a morality of moderation at the top, and generosity to middle and lower-income workers tiers. But this next time we must be inclusive of all races, and if we do, we will be proud of the country America will become.

Thank you

Comments